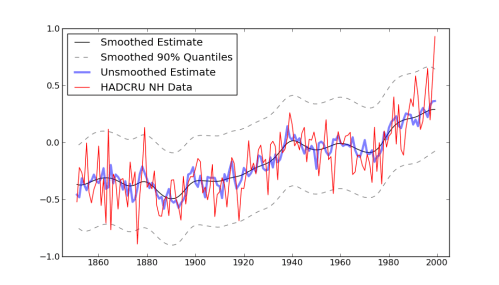

Two weeks ago, I slapped together a post about the banana distribution and some of my new movies sampling from it. Today I’m going to explore the performance of MCMC with the Adaptive Metropolis step method when the banana dimension grows and it becomes more curvy.

To start things off, have a look at the banana model, as implemented for PyMC:

C_1 = pl.ones(dim)

C_1[0] = 100.

X = mc.Uninformative('X', value=pl.zeros(dim))

def banana_like(X, tau, b):

phi_X = pl.copy(X)

phi_X *= 30. # rescale X to match scale of other models

phi_X[1] = phi_X[1] + b*phi_X[0]**2 - 100*b

return mc.normal_like(phi_X, 0., tau)

@mc.potential

def banana(X=X, tau=C_1**-1, b=b):

return banana_like(X, tau, b)

Pretty simple stuff, right? This is a pattern that I find myself using a lot, an uninformative stochastic variable that has the intended distribution implemented as a potential. If I understand correctly, it is something that you can’t do easily with BUGS.

Adaptive Metropolis is (or was) the default step method that PyMC uses to fit a model like this, and you can ensure that it is used (and fiddle with the AM parameters) with the use_step_method() function:

mod.use_step_method(mc.AdaptiveMetropolis, mod.X)

Important Tip: If you want to experiment with different step methods, you need to call mod.use_step_method() before doing any sampling. When you call mod.sample(), any stochastics without step methods assigned are given the method that PyMC deems best, and after they are assigned, use_step_method adds additional methods, but doesn’t remove the automatically added ones. (See this discussion from PyMC mailing list.)

So let’s see how this Adaptive Metropolis performs on a flattened banana as the dimension increases:

You can tell what dimension the banana lives in by counting up the panels in the autocorrelation plots in the upper right of each video, 2, 4 or 8. Definitely AM is up to the challenge of sampling from an 8-dimensional “flattened banana”, but this is nothing more than an uncorrelated normal distribution that has been stretched along one axis, so the results shouldn’t impress anyone.

Here is what happens in a more curvy banana:

Now you can see the performance start to degrade. AM does just fine in a 2-d banana, but its going to need more time to sample appropriately from a 4-d one and even more for the 8-d. This is similar to the way a cross-diagonal region breaks AM, but a lot more like something that could come up in a routine statistical application.

For a serious stress test, I can curve the banana even more:

Now AM has trouble even with the two dimensional version.

I’ve had an idea to take this qualitative exploration and quantify it to do a real “experimental analysis of algorithms” -style analysis. Have you seen something like this already? I do have enough to do without making additional work for myself.