A short note on the PyMC mailing list alerted me that the Apeescape, the author of mind of a Markov chain blog, was thinking of using PyMC for replicating some controversial climate data analysis, but was having problems with it. Since I’m a sucker for controversial data, I decided to see if I could do the replication exercise in PyMC myself.

I didn’t dig in to what the climate-hockey-stick fuss is about, that’s something I’ll leave for my copious spare time. What I did do is find the data pretty easily available on the original author’s website, and make a translation of the R/bugs model into pymc/python. My work is all in a github repository if you want to try it yourself, here.

Based on Apeescape’s bugs model, I want to have where

, with priors

and

.

I implemented this in a satisfyingly concise 21 lines of code, that also generate posterior predictive values for model validation:

# load data

data = csv2rec('BUGS_data.txt', delimiter='\t')

# define priors

beta = Normal('beta', mu=zeros(13), tau=.001, value=zeros(13))

sigma = Uniform('sigma', lower=0., upper=100., value=1.)

# define predictions

pc = array([data['pc%d'%(ii+1)] for ii in range(10)]) # copy pc data into an array for speed & convenience

@deterministic

def mu(beta=beta, temp1=data.lagy1, temp2=data.lagy2, pc=pc):

return beta[0] + beta[1]*temp1 + beta[2]*temp2 + dot(beta[3:], pc)

@deterministic

def predicted(mu=mu, sigma=sigma):

return rnormal(mu, sigma**-2.)

# define likelihood

@observed

def y(value=data.y, mu=mu, sigma=sigma):

return normal_like(value, mu, sigma**-2.)

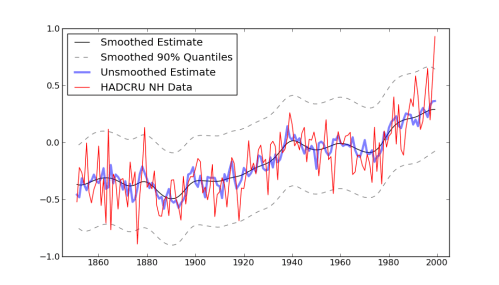

Making an image out of this to match the r version got me stuck for a little bit, because the author snuck in a call to “Friedman’s SuperSmoother” in the plot generation code. That seems unnecessarily sneaky to me, especially after going through all the work of setting up a model with fully bayesian priors. Don’t you want to see the model output before running it through some highly complicated smoothing function? (The super-smoother supsmu is a “running lines smoother which chooses between three spans for the lines”, whatever that is.) In case you do, here it is, together with an alternative smoother I hacked together, since python has no super-smoother that I know of.

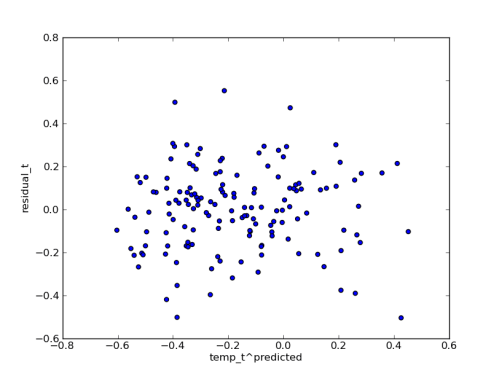

Since I have the posterior predictions handy, I plotted the median residuals against the median predicted temperature values. I think this shows that the error model is fitting the data pretty well: